In Search of Sir Hubert

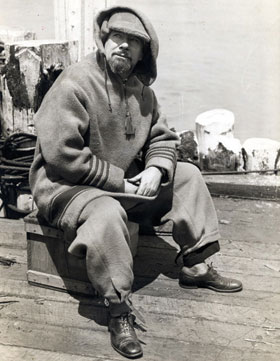

Australia’s “other” polar hero still remains something of a mystery to his hero-worshipping countrymen.

While his Australian contemporaries, Sir Douglas Mawson and Frank Hurley enjoy the modern notoriety of their achievements during the “heroic age” of polar exploration, the equally breath-taking exploits of the adventurous boy from Adelaide, Sir Hubert Wilkins, are often overlooked.

Born in 1888 in South Australia’s scenic Clare Valley, Hubert Wilkins was the youngest of the ‘golden era’ explorers. (Hurley 1885, Mawson 1882). Driven by the desire for adventure and an escape from the harsh rural life on Australian Victorian-era farms during the historic drought of 1895-1902, Hubert also believed he could improve the lot of farmers with better long-term weather forecasting and ecological management.

His family, stricken by the drought, moved to Adelaide in 1903, but Hubert, fascinated by the world as a whole, was in Sydney by 1909 working as a newsreel cinematographer. This took him to England and later the Balkan War in 1912, where he is credited with creating the first ever movie footage of actual battle scenes.

On his return to London, he joined the ill-fated 1913 Canadian Arctic Expedition mounted by the notorious Vilhjamur Stefansson. When Stefansson abandoned his men on the Karluk, stuck fast in the polar ice, Wilkins escaped with his leader to Point Barrow, Alaska, to discover the world engulfed in war. He returned to his earlier vocation of war correspondent and, unlike the more famous Frank Hurley, Wilkins was twice decorated for bravery whilst filming forward of enemy lines on the Western Front in 1917.

After the war, he joined the All-Australian crew (ironically in place of the unqualified Sir Charles Kingsford Smith) for the England-to-Australia air race in the quest for the 10,000 pound reward offered by the Australian Government. His aircraft, a Blackburn long-range bomber named the “Kangaroo” crashed in Crete with engine trouble.

Wilkins next turned to the Antarctic, but his efforts began badly with the ineffectual Cope Expedition of 1920 and Shackleton’s tragic death aboard Quest in 1922. Despite this, the British Museum rewarded him with his own two-year expedition to the Australian outback.

It was his next exploit that gained him international recognition - and his knighthood. With Pilot, Carl Ben Eielson, he flew a single-engined Lockheed Vega from Alaska to Spitsbergen, the first such flight. In another ironic twist, Kingsford-Smith flew one of the heavy Fokker Trimotors Wilkins rejected for Arctic duty across the Pacific Ocean into the history books.

Back in Antarctica in late 1928, Wilkins, Eielson and their trusty Vega, now fitted with floats, flew mapping sorties over Graham Land (Antarctic Peninsula) from Deception Island and the pair became the first to fly over the continent as well as map uncharted land from the air.

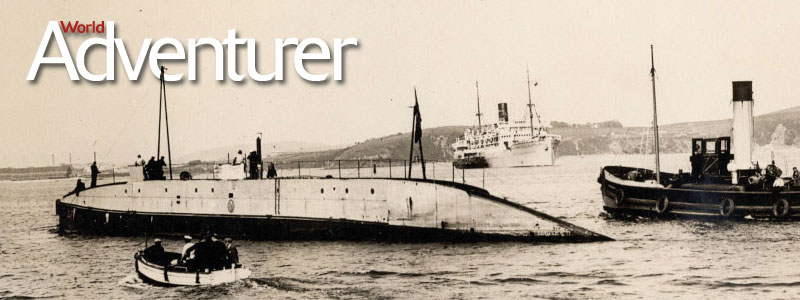

After another history-making, around-the-world journey aboard the Graf Zeppelin in 1929, Wilkins embarked on his most ambitious and perhaps foolhardy attempt in 1931. He wanted to prove (and be the first) that submarine travel was possible under the Arctic ice cap. Unfortunately his choice of craft, a pensioned-off ex-WW1 US ‘O’ Class submarine, renamed Nautilus, was not up to the task. His crew, upon learning of Wilkins’ plans, partially disabled the craft to prevent, what they reasonably believed, would be a suicide mission. He was, however, able to prove that a submarine could work beneath the polar ice and some thirty years later the world’s first nuclear-powered submarine, appropriately named Nautilus, did reach the North Pole completely submerged.

After this, Wilkins went on to further map Antarctica by air with the millionaire explorer, Lincoln Ellesworth. Unable to find work at home in Australia, he contracted himself to the US Military during WWII in a variety of roles including espionage and Arctic survival.

Despite his impressive list of ‘firsts’ and pioneering adventures, the proudly patriotic Sir Hubert Wilkins remains sadly overlooked by a country that so reveres its heroes. In the end, it was the US who took his ashes to the North Pole aboard the submarine USS Skate on 17 March 1959.